Note from Changing the Narrative Cell 3

Summary of key points

Neoliberalism had been founded on a narrative based around values and a values-based approach would be needed to counteract it.

We should be more confident in appealing to the values of benevolence and universalism and should not try and adjust our messages to people’s different values.

Our narrative needed to be a dialogue with the public and different groups with it, authentically connecting with them and highlight authentic experiences and voices.

In more detail

Steve Wyler, Co-convenor of a Better Way, began by recapping on some of the main points from previous meetings:

The current national narrative can ‘other’ people and portray them as part of the problem, and organisations which seek to help them can inadvertently do this too.

Creating platforms for authentic voices who frame their own story can help disrupt existing narratives and shift power, and organisations can help by linking these stories to systemic issues and solutions as well as individual stories.

The new narrative we’d like to create will portray people as part of the solution, not the problem and, as part of this, we need to tell a different story of responsibility to each other, mutual obligation and caring for each other, as well as highlight the need for systemic change. This needs to appeal to people of different political persuasions if it is to take hold.

He said that the topic of today’s discussion was ‘How do we bring about change’ and introduced our speaker, Tom Crompton, from the Common Cause Foundation, to talk about the role of values in achieving change.

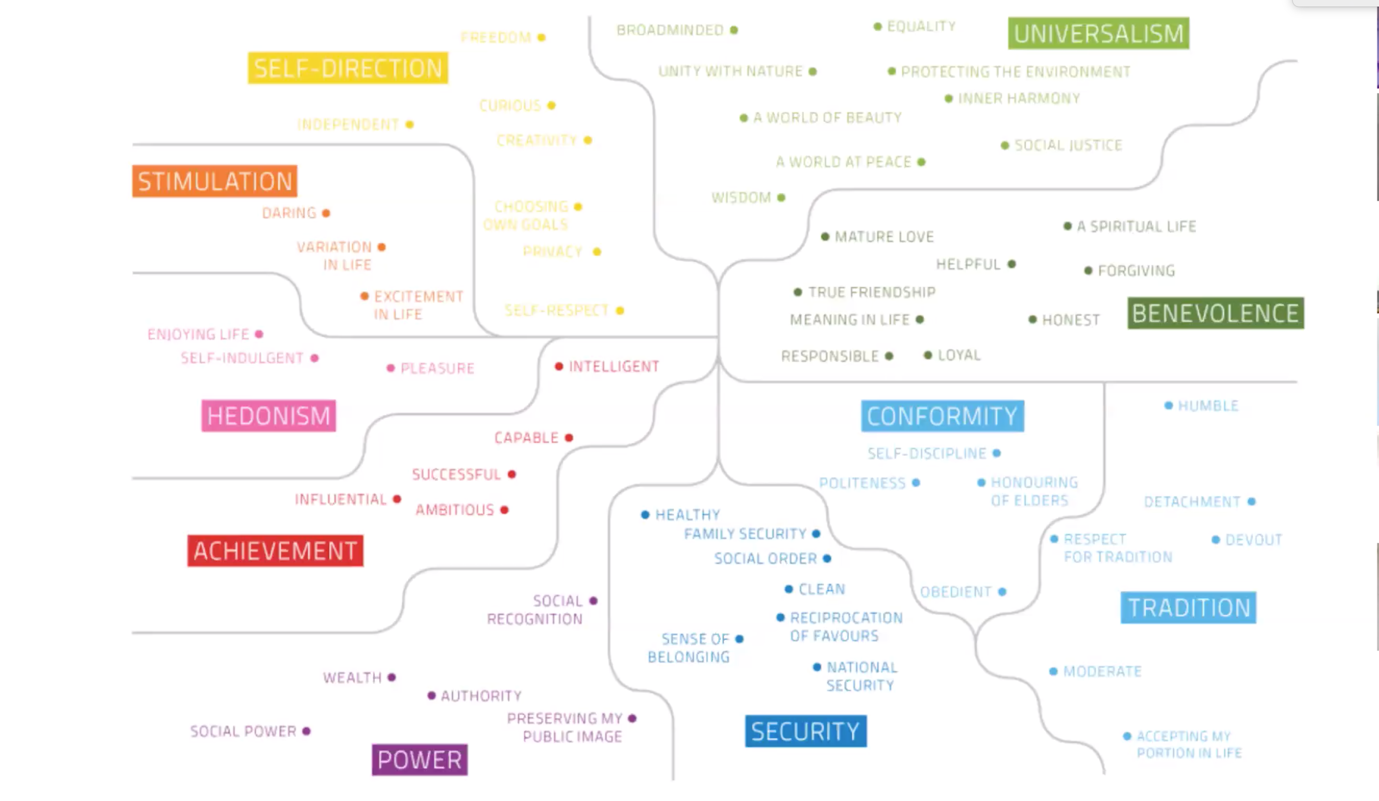

Tom said that they had created a model of values, drawing on academic work in social psychology and surveys where they had asked people in a hundred countries what they valued in life. Clear patterns emerged that have strong predictive value, as shown in the ‘map’ below; and the values had been used successfully in communications to influence people to support environmental causes.

These values tend to cluster, with people associating with those adjacent in the map to the one they most identify with. But they are not static and in practice everyone shares all the values to some degree or other.

Conventional communications wisdom is that you should ‘speak the language’ of those you want to influence and segment audiences with different messages for each. But the lesson from their work is that if you draw attention to one value it tends to elevate the recipients attachment to that value. Experiments have clearly demonstrated a short-term effect but there is probably also a longer term one which has not yet been measured.

So, for example, it is better not to stress economic arguments in relation to the environment or disability issues, even for those who most naturally associate with that value, and more advantageous to use values of universalism and benevolence.

They had also found that an appeal to people’s values cuts through better than campaigns that focus on the head.

He noted that it was common to build out from the values of benevolence to reinforce values around conformity and tradition, with a short step to security, and far less common to build out from benevolence to universalism. In thinking about shifting the narrative, we could do more of that and with greater confidence.

In breakout groups and the subsequent discussion the following points were made:

The map was useful to understand what was happening, and we agreed that it was good to speak the language of values, but people in the group wanted to avoid being manipulative. We were not engaged in marketing.

Sometimes members of the group had found it useful to appeal to the values of different parts of the map, for example, arguments around the economic and personal advantages of equality strategies had gained traction and led to policy change.

Using values could help people to engage in a conversation to bring about change. It was important to recognise that the polarisation of left and right did not necessarily reflect people’s values and that people had more values in common than we tend to think.

Neo-liberalism had been very successful in establishing a narrative based around values on the lower left-hand side of the map and a shift in that narrative also needed to be values based, starting from a different point.

A radical new narrative was needed focusing on universalism and benevolence and emphasising responsibility, enabling self-direction.

Our narrative needed to be a dialogue. One-to-one conversation between people can be the foundation to move into a new more relational narrative space.

It was important to tell authentic stories and to listen to the public and what matters to them. This tended to be things like home, family, place and where they work.

This dialogue is not the same as focus group politics. Radical listening skills are required, and discussions with a wide range of people, allowing their agendas to come to the surface, with sufficient trust to allow challenge and criticism to be expressed.

Note from Changing the Narrative Cell 2

Note of the changing the narrative cell, 21 July 2020

Summary of key points

A drive for more funding can reinforce problematising narratives but it is possible to tell the story of change in ways that show where the need lies but does not disempower or problematise those who are supported.

Creating platforms for authentic voices who frame their own story can help disrupt existing narratives and shift power.

The media can problematise and ‘other’ people but can also be part of the solution – we can help them tell ‘human interest’ stories that show systemic issues and solutions as well as individual stories.

Individualism is part of the problem. We need to tell a different story of responsibility to each other, mutual obligation and caring for each other, as well as highlight the need for systemic change. This needs to appeal to people of different political persuasions if it is to take hold.

Funders can be part of the solution, for example, bringing in people with lived experience to help them make good choices.

Next time we will look in more detail into how to make change happen.

In more detail…

Steve Wyler started the meeting by summarising the key points from the last:

We want the national conversation to shift from 'them and us' to caring for each other, in which everyone contributes and also has responsibilities.

We need to create platforms for people to tell stories where they are the heroes, not our services.

We need to use new language, for example ‘valuable’ not ‘vulnerable’.

He said that at this meeting we were going to focus on the barriers to this kind of narrative and what we can do about them.

Neil Crowther reminded us of some the issues he’d raised previously, including the quote from a school nurse who had heard a boy during lockdown say that he was in school because he was ‘valuable’: that switch from seeing people as ‘vulnerable’ to focusing on their assets was a key shift in the narrative we are seeking. Other shifts were to hope, not fear, what we stand for, not what we are against, to solutions and opportunities, not threats, and support for everyday heroes. There is often a significant gap between the dominant narrative now, and the story we want to tell eg ‘social care as a vehicle for a good life’ rather than ‘social care as a destination or a place’.

Neil identified some of the barriers to and challenges for this kind of narrative:

For charities, fund-raising from the public was perceived to work best when describing problems and the agencies as the saviours.

Likewise, commissioners, procurers and charitable funders often wanted organisations to demonstrate the problem and show how their investment had solved it.

Influencing politicians to spend more on social issues often leads campaigners to play up the negatives and to portray services as solution, and in an age of austerity many services were under-funded.

Duncan Shrubsole then gave his perspective based not just on his current role at the Lloyds Bank Foundation but also as the Chair of Switchback and his 9 years at Crisis. He agreed that fund-raising was a challenge but added that the best charities do already major on turning lives around, but to get public buy-in they also have to tell the story of the journey individuals have gone through, including the negatives, and they have to show where they add value. That story had to be told in a humanising, empowering way. Likewise, when talking about issues with the government, who are trying to target tight resources, it is important that they understand and correctly identify needs. They have to understand the challenges people face.

There was sometimes a danger, Duncan said, that asset-based narratives reinforce a view that solutions were always in the hands of individuals. Promoting agency is important but this has to be balanced by also describing and addressing systemic issues that may hold people back. JRF described this a moving away from individual deficits to talking about what is holding people back. We do need people to be able to express injustice and harm, and for the narrative to identify what is getting in the way and what we can do about it.

Points coming out of the subsequent discussion included:

Creating platforms for authentic voices changes the narrative. It is important that the stories that are told stay true to people, and that people telling their stories are ‘talking in voice’, not mediated by others. Genuine voices disrupt the process. Sometimes charities frame stories in ways that justify what they do, when in fact they are not doing the right thing. The bigger picture is that people lack power, which is too concentrated in the state and vested interests, and giving people the opportunity to express an authentic voice can disrupt and shift this. Fixers helped people tell their own story in short films, with the framing done by themselves – see below. Sound Delivery is also providing platforms for lived experience– see below. Sometimes people don’t see value in themselves and lack aspirations or a feeling of agency. Grapevine Coventry and Warwickshire is training the people they work with to become the ‘leaders of the future’.

Targeting the media. We need to disrupt national narratives in the media and elsewhere which can be ‘othering’, disempowering and problematising. We should look not to news outlets but also daytime TV and popular magazines.

Telling the story of the system, not just the individual. Story-telling is important but it needs not to be just a human interest crisis story, it also needs to show what is wrong with the system in ways that point to solutions. Cathy Come Home is a famous example of how a story could lead to systemic change, in this case the Homeless Act. JRF is not trying to tell the story of poverty in a deeply human way, for example.

Reinventing society. The agenda of individualism underlies the current narrative and in the new framing we need to appeal to people to think beyond themselves and also not look to the state where family or grass roots support in communities might be a better solution.

A cross-party narrative of responsibility, caring for each other and mutual obligation. We need a narrative that crosses political divides if it is to take hold. Responsibility towards each other is part of the narrative of people caring for each other: you step forward to surface and resolve an issue because you want to prevent others from experiencing the same problem. Responsibility, linked to mutual obligation, is a concept that appeals to people of different political beliefs, whereas appeals for systemic change alone are often perceived as left wing. Taking responsibility is part of taking control and developing agency. The narrative needs to recognise that people do have choices, sometimes they make the wrong ones and have to take responsibility for that, but the system can also block opportunities or be unfair.

Supportive funders. Funders can be part of the problem, but sometimes they are blamed by charities when it’s not their fault. Some funders are trying to work in a different way, for example, democratising ways of distributing funds and bringing in people with lived experience to help them make choices.

It was agreed that the next meeting, which is at 3.00 -4.30 pm on 7 September, would focus on the practical dimension of how to change the narrative, and we might explore some specific examples.

Some relevant links

Fixers – see this blog by Margo Horsley.

Sound Delivery – links kindly provided by Jude Habib below:

An evaluation of our spokespersons network pilot – funded through crowdfunding and match funded via support from PHF and Lankelly Chase. We are now in conversations with funders to scale up from the pilot: https://beingthestory.org.uk/spokesperson-network

Two people from our network Brenda and Amanda featured on a Radio 4 Documentary – Unchained – about women and the criminal justice system https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000hghf

Being the Story Podcast – This podcast gives a platform to range of individuals with lived experience of a range of social issues – Think TedTalks for the Social Sector – available on all podcast platforms: https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/being-the-story/id1483449674 reflects the work to build confidence, find platforms and encourage visibility for those often not listened to.

Note from Changing the Narrative Cell 1

First meeting of the Better Way ‘Changing the Narrative’ cell, 25 June 2020

Summary of key points

We want the national conversation to shift from 'them and us' to caring for each other, in which everyone contributes and also has responsibilities.

We need to create platforms for people to tell stories where they are the heroes, not our services.

We need to use new language, for example ‘valuable’ not ‘vulnerable’.

At future meetings we are going to focus on the barriers to this kind of narrative and what we can do about them.

2. In more detail

Steve Wyler, co-convenor of a Better Way, explained that we hope the new cell will not only enable participants to share insights with each other but will also provide material that we can share with the wider network. The group had been set up to explore further the Better Way Call to Action bullet point - ‘to see the potential in everyone and stop services becoming a ‘problem industry’ – also reflected in the Better Way principle ‘building on strengths is better than focusing on weaknesses’.

There were three levels to the change a Better Way would like to see, he explained:

Individual practitioners to change their relationship with those they serve;

Providers of services in the voluntary and public sector to stop using narratives which present people as problems or ‘vulnerable’;

Government and opinion formers to stop using a national narrative which too often portrays recipients of welfare and people experiencing poverty or issues in their lives negatively.

The group would be focusing primarily on the last two – how to change the overall narrative.

He introduced Neil Crowther from Social Care Future, who had agreed to act as what we are calling a ‘thought leader’ for the group. His presentation included these points:

The language we use, the ‘framing’ is incredibly influential, reinforcing familiar stories and emotions which influence how we see things e.g. talking of crime as a ‘virus’ points to social solutions, as opposed to presenting it as a ‘beast’, which points to police intervention.

Hopeful narratives are empowering, and ways to foster hope include focusing on solutions, opportunities and what we stand for as well as emphasising the role of everyday heroes.

Social Care Future is seeking to shift the narrative which currently presents social care as being in crisis, broken and about to collapse and which puts the sector centre stage, not the people served, presenting it as a Cinderella service. We talk of caring for the ‘vulnerable’, which creates a them and us.

Talk of the ‘vulnerable’ has peaked in the Covid-19 crisis but another story has also emerged, of mutual aid and caring about each other, not just caring for.

The latter provides a different basis for how we think about people in the adult social care system, and indeed elsewhere – as caring for each other, reciprocity, ‘valuable rather than vulnerable’. Reciprocity is key, where instead of offering someone help, you ask them for a favour.

We need to look at who are the heroes of our stories, and who is telling it? Is it the professional, or the agency, or the people whom they serve? It should be the latter.

Looking at the wider national conversation, and the stories service providers tell about those they work with, he hoped we could move to a hopeful narrative of solidarity, in which we care for each other, and in which we foster a sense of agency, rather than painting people as problems.

As an example, he showed an advert made by NSPCC which portrayed a boy supported by the charity as achieving his dream of becoming an astronaut.

We then broke into three breakout groups to consider ‘What is the story we want to tell?’ These were some of the points made in the following discussion, facilitated by Caroline Slocock, Better Way co-convenor:

There was broad agreement about the need for a new narrative around mutual support, breaking down the ‘them and us’ and telling a story of ‘all of us’ which can help to build agency.

We have seen how digital tools can democratise storytelling, especially among young people.

We should avoid presenting people as ‘case studies’ and stereotyping them. It is important to give power to people to tell their own stories in their own language, whilst also managing risks and practising safeguarding.

That often involves giving up power and instead creating platforms for others. Too often, organisations working with people feel that ‘they know best’ and this is a holding on to power. They are attracted to ‘rescuer narratives’ which cast the organisation as the hero in the story. They encourage people they work with to tell a negative story about themselves, e.g. the homeless young person retelling their sad story, and this reinforces rather than helps to overcome problems.

Changing the narrative also requires a culture and systems change and this cannot be done by one organisation in isolation. We need to work together on this.

The people who have experienced difficulties in their lives are often incredibly resilient and strong, but we insist on presenting them as vulnerable.

Stories have heroes as well as villains. The system should be the villain, not the individual, but too often we blame them.

Language was important and often got in the way. It is hard to change our own internal narratives.

We should look at the bigger picture of a culture of individualism over the last 40 years which is all pervasive and which underplays the importance of relationships and how people find fulfilment through them. We need to emphasise the responsibility we have toward each other and also help people find their sense of purpose.

Next time the group wanted to look at the barriers to the hopeful narrative of mutual help – what stands in the way of making it happen, and what can we do about it.

3. Dates of next meetings:

Tuesday 21 July, 3.00-4.30pm

Monday 7 September, 3.00-4.30pm

4. Further reading/viewing

Neil Crowther shared some links after the meeting:

The Vulnerables – an article by disability rights campaigner Baroness Jane Campbell.

A selection of various podcasts and blogposts at #socialcarefuture

An example of someone who uses services being heard: Anna Severwight reframing the discussion on funding at the Commons Health and Social Care Committee

Margo Horsley shared some links which describe the work of Fixers, an initiative (no longer running) which enabled young people to tell their stories, and to be heard, understood and respected by others.

What is Fixers: https://youtu.be/39sYPhAg-Sw.

Some fixers reflecting: http://www.fixers.org.uk/index.php?page_id=3244.

National platforms: http://www.fixers.org.uk/feel-happy-fix/fixing-child-sexual-exploitation/home.php .

A campaign on sex education in schools (the Government Minister at the time, Maria Miller, believed that it was individual voices that had made change happen despite all the work put in by other institutions over the years): http://www.fixers.org.uk/index.php?module_instance_id=11208&core_alternate_io_handler=view_news&data_ref_id=16291

Note from a network discussion: Better Way Politics

Better Way Politics – note of a discussion among Better Way members, 7th November 2018

Politics has become a dirty word, and many people don’t want to have anything to do with it. And yet the ancient Greeks had a word for private individuals who were foolish enough not to engage in the public world of politics: idiotes. Members of the Better Way are starting to imagine what a different, healthier form of politics might look like, what mechanisms might help, and what might attract more people – including the next generation – to want to play a part in political life.

1. What is wrong with politics?

We sense that politics as currently practised makes it difficult for Better Way practices to flourish.

This is partly because the system of party politics at national and local levels means that politicians, whatever their good intentions, feel compelled to demonstrate their effectiveness through command and control behaviours, often peddling false certainties, and trading people’s welfare for votes.

It is also, more fundamentally, because of the way in which everyday political discourse takes place, policy is formed and decisions are made, with suitably qualified ‘professionals’ in the dominant role, and most people feeling alienated from the political processes that frame their lives.

We believe that the politics we have at present generates an ‘us and them’ mindset, and the consequences are pervasive across our public culture and our public services. We can see this in how systems operate, how things are measured, how people are treated, and the effect is dehumanising. From the perspective of a ‘service user’ the behaviours which our politics ultimately produce are deeply unsatisfactory, as demonstrated in a blog from Love Barrow Families (which works in Barrow-in-Furness with families facing multiple and severe disadvantage):

‘How can you be expected to build a relationship and come to understand each other if it’s already geared up for termination? The person will know that you’re not truly present and not connected to them. Professionals don’t like words such as ‘relationship’ or ‘connection’. They don’t want to be connected to what they see. You can watch professionals trying to hide their own disgust. They become immobile and take on the appearance of someone who has found themselves in the wrong room. They subtly, without the individual knowing, try and find the room that they should be in. And it doesn’t work. The quieter they try to do it, the louder it becomes. They can’t get past their own history and history is never quiet. Just because it isn’t spoken doesn’t mean it isn’t heard. People create systems for this reason until the systems become fluent enough to manage their own anomalies. Rules are issued. Specialised people are brought in to root out values. Values are for walls, front doors and funders. They’re not for the people who desperately need the service. Organisations don’t want you to belong. They want you for your vital statistics. They want you when the humans come to look at the animals in the zoo. Questionnaires, scales of one to ten. Ticks in boxes and tallied at the bottom. Tables consulted. You are this, you are that. People will look for a diagnosis and willingly take anything. It’s what they want and services give it to them. Then they can go out into the world and say,” I am this”. And the world says,” so what, it’s meaningless”. If you’re set up to only look for the symptoms then that is all you will treat. And they will be back because the central issue hasn’t been addressed. Belonging is clouded by issues in orbit. Services target the issues and not the belonging.’

We can also observe the ‘primacy of pain’ in public policy. Painful stories are exploited by a prurient media, and by politicians needing to make an impact, and by public services (including charities) needing to justify their existence, and so they form the basis of much policy making. This is essentially a deficit model, focusing on (and ultimately reinforcing) the worst not the best.

2. What are the alternatives?

Here are two responses:

‘The whole system of democracy needs to be redesigned, with different distributions of power, different means of assigning political legitimacy, devolution of all powers capable of remaining local, extended enforcement of universal human rights. We simply cannot rely on the supreme authority of a single selectorat claiming legitimacy merely by mass vote-casting systems’ (Roger Warren Evans)

Maybe we could argue for a different kind of approach to policy-making, which is less certain, less media driven, less dualistic, more ambiguous, tentative, diverse, respecting of many different expertises and perspectives, more attentive and listening, comfortable with not-knowing, accepting that success and failure come in many guises. In other words, a non-political (with respect to today's model of politics) policy-making. (Charity sector leader)

We reminded ourselves that we are not striving towards a ‘perfect’ political model and that all attempts to establish Utopia have ended in disaster. Any system of Better Way politics needs to accommodate imperfection, learning, and change.

Many of us feel that the more that public policy making can be localised, the better. Debate and decision-making among people who know each other, and have some appreciation of the context of each other’s lives, could help build a better form of politics. But this by itself is not the whole answer: we acknowledge that proximity does not necessarily produce connection, trust, or respect, and not all political questions can be determined at neighbourhood level.

Various forms of participatory democracy can create opportunities for many more people to participate in debate and decision-making. But allowing more voices to be heard is not of itself sufficient – inequalities and concentrations of power can persist within participatory democracy, with some voices dominating over others.

An important starting point is the recognition of one’s own vulnerability. We must allow ourselves to feel our own powerlessness, unknowing and vulnerability in the face of theirs. Without that first step, little else is possible.

3. Power

As Elinor Ostrom has argued, in any group there will be a majority in favour of co-operation, but also a greedy minority who will act to take over. Therefore, it will always be necessary to challenge concentrations of power. There are many mechanisms to do so (an independent judiciary, a free media, proportional representation, a second chamber, an impartial civil service, regulatory bodies, the work of civil society agencies, for example), and these are always under pressure from vested interests, who want to remain in control for their own advantage.

However, we felt that a focus on power alone may not be the way to build a Better Way politics. After all, power is not a fixed quantity and it ebbs and flows. In physics power is the rate at which energy is transferred, rather than something possessed by an entity. In many senses politicians and political institutions are less powerful than they would like to believe.

While recognising widespread inequalities and concentrations of power, we need a different foundation for a Better Way politics, one which is less adversarial and starts with the notion of ‘humans helping other humans’ rather than the notion of ‘some humans controlling others’. We shared some ideas of what this might this look like:

Integration: in the face of increasing fragmentation and complexity a core political goal should be to achieve a more connected society.

Our practice of politics should be founded upon a shared understanding of the needs we all have, as set out for example by the Centre for Non-Violent Communication (see Annex).

Those responsible for designing systems of support should recognise that ultimately people want people who are not paid to be in their lives.

Those in leadership roles in political life should foster adult to adult relationships (not parent to child).

Political decision-making should be decentralised where possible, according to the notion of subsidiarity, with a willingness to design in local difference (a postcode choice not a postcode lottery).

We need a shift in educational practice, in order to bring up a next generation of citizens who have an understanding of their interconnectedness as human beings, have positive strategies to respond to conflict, and also have the belief and confidence that they can change things for the better, that it is possible to be constructively disruptive of prevailing systems.

4. Sortition

We also discussed the idea of ‘sortition’ (the use of random selection to populate a decision making assembly), and we believe that this can be extended to other aspects of political life beyond jury service, which is one of our few public institutions which retains general public confidence.

We understand that juries are effective in the criminal justice system for several reasons:

They enshrine a popular principle (that we are all equal before the law);

They are associative (a group of twelve people is needed to reach a common decision);

They have access to advice from people with a depth of professional knowledge (barristers, expert witnesses, judges, court clerks).

We think that if sortition were to become more widespread in political life equivalent mechanisms would be needed to maximise the chance for success. We felt it would be useful to engage those with greater expertise on this subject (eg Involve, Sortition Foundation etc).

Note from Better Way London Cell: Grenfell Tower - what stories will be told?

Note from Better Way London cell 1 – 13 July 2017

We think that what happened at Grenfell has the power to significantly influence the post-Austerity narrative which has just begun to be opened up and it will undoubtedly shape future policy on social housing and possibly public services in important ways. We’ve been here before. We were reminded about The Story of Baby P which documented what actually happened but also found that it was the ‘political story’, rather than the facts, that shaped the changes in social policy that followed, and not necessarily for the good. This is something we think is likely to happen in the case of Grenfell. We’d like to influence that narrative if we can.

There are clearly many angles to the Grenfell story, with vested interests seeking to skew things in various directions (eg national government wanting to highlight local authority failures). Some elements of what happened will only be clear once the facts are fully established. But what is evident now is that the voices of residents, who had been raising concerns in their building for years, were not heard and their expertise based on lived experience was undervalued.

This is in contrast to what happened at Ronan Point (as documented by Frances Clarke from Community Links in the Guardian). There, residents and campaigners - aided and amplified by Community Links, an architectural expert and his students and the Evening Standard – managed to get the building tested and eventually demolished, along with many others like it across the country (though this was only half a success, as wider lessons were not learnt, as demonstrated by the recent tragedy). One of the campaigners in Glasgow remains active to this day, and in Glasgow building standards in tower blocks are apparently higher today.

The moral of these two stories, we thought, was that society would be so much better if we can get the best out of all of us. What happened after Grenfell does illustrate this to a degree, despite the chaos and terrible weaknesses it also exposed. The many acts of kindness, the breakdown of communication barriers between rich and poor local residents as a result of individual and corporate acts of care, the individual voices that have now been heard in the media, these have all led to insights that before were lacking and new potential alliances. The human right to a safe place to live, which has been lost in the tangle of what looks like weakened regulation and enforcement, limited budgets and possible profiteering, has risen to the surface again.

It is so easy to see the Grenfell story in terms of conflict, eg rich versus poor, state power versus citizen’s rights - and there may be justication in this. But we all agreed that this was potentially a “teachable moment” in which new inclusive alliances could be built, unexpected allies created, and fundamental rights acknowledged and protected. In the face of understandable anger, it is important not to assume that everyone else is the enemy or to assert that one party has a monopoly on the truth: others, also, have insights into what has happened and forensic approaches to establishing the facts are important, alongside the need for empathy and listening to those who have suffered.

Ronan Point was demolished because of a coalition between those who had expertise through lived experience (eg residents who could smell cooking through the floor from two stories down who knew therefore that any fire could not be fully self-contained, despite “expert” assurances to the contrary) and experts, academics and the media. If this could have happened when local residents raised concerns in Grenfell Tower, perhaps the tragedy would have been averted.

It is often true, as Danny Kruger argues in his Spectator think piece, that change ultimately only happens when one member of the elite persuades the rest of the elite, but such change is far more likely to happen when these kind of coalitions are built and in particular where local people are given power in the debate. This is not a matter of “giving” people’s voices, or enabling them to speak, we thought. People already have voices and in the era of social media have no difficulty expressing that voice. Indeed, the residents of Grenfell Tower were articulate and well informed and had made their points persistently.

The shift needed here is to create cultures and environments in which those voices are heard. Public services and politicians struggle to hear within existing structures and constraints and need support and facilitation. Papers like the Sun and Daily Mail can appear to be the enemy but could be an important force, if harnessed. It is a core role of the voluntary sector to help voices be heard, we observed. But it is not doing this job well, we thought (though this was not the case with Community Links and Ronan Point).

Finally, an interesting point about backlash and Ronan Point. Local people who were homeless in B & Bs were very angry with those who wanted to demolish Ronan Point as they just wanted a roof over their heads and this frustration broke out in destructive ways. This may happen again. Their voice must be heard too if Grenfell is not to result just in widescale demolition in a way that simply fuels the housing crisis and results in currently homeless people being pushed further down the waiting lists.