Note from Changing the Narrative Cell 3

Summary of key points

Neoliberalism had been founded on a narrative based around values and a values-based approach would be needed to counteract it.

We should be more confident in appealing to the values of benevolence and universalism and should not try and adjust our messages to people’s different values.

Our narrative needed to be a dialogue with the public and different groups with it, authentically connecting with them and highlight authentic experiences and voices.

In more detail

Steve Wyler, Co-convenor of a Better Way, began by recapping on some of the main points from previous meetings:

The current national narrative can ‘other’ people and portray them as part of the problem, and organisations which seek to help them can inadvertently do this too.

Creating platforms for authentic voices who frame their own story can help disrupt existing narratives and shift power, and organisations can help by linking these stories to systemic issues and solutions as well as individual stories.

The new narrative we’d like to create will portray people as part of the solution, not the problem and, as part of this, we need to tell a different story of responsibility to each other, mutual obligation and caring for each other, as well as highlight the need for systemic change. This needs to appeal to people of different political persuasions if it is to take hold.

He said that the topic of today’s discussion was ‘How do we bring about change’ and introduced our speaker, Tom Crompton, from the Common Cause Foundation, to talk about the role of values in achieving change.

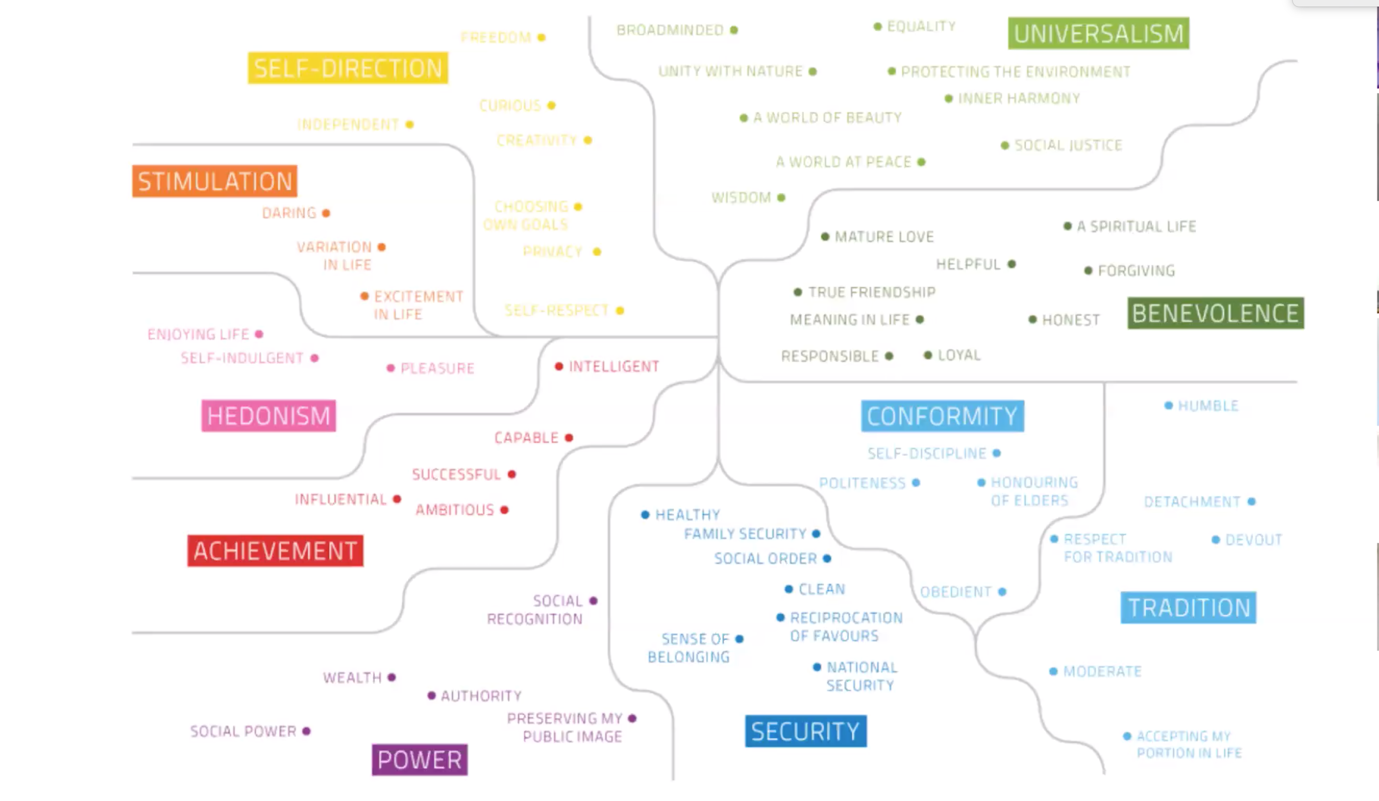

Tom said that they had created a model of values, drawing on academic work in social psychology and surveys where they had asked people in a hundred countries what they valued in life. Clear patterns emerged that have strong predictive value, as shown in the ‘map’ below; and the values had been used successfully in communications to influence people to support environmental causes.

These values tend to cluster, with people associating with those adjacent in the map to the one they most identify with. But they are not static and in practice everyone shares all the values to some degree or other.

Conventional communications wisdom is that you should ‘speak the language’ of those you want to influence and segment audiences with different messages for each. But the lesson from their work is that if you draw attention to one value it tends to elevate the recipients attachment to that value. Experiments have clearly demonstrated a short-term effect but there is probably also a longer term one which has not yet been measured.

So, for example, it is better not to stress economic arguments in relation to the environment or disability issues, even for those who most naturally associate with that value, and more advantageous to use values of universalism and benevolence.

They had also found that an appeal to people’s values cuts through better than campaigns that focus on the head.

He noted that it was common to build out from the values of benevolence to reinforce values around conformity and tradition, with a short step to security, and far less common to build out from benevolence to universalism. In thinking about shifting the narrative, we could do more of that and with greater confidence.

In breakout groups and the subsequent discussion the following points were made:

The map was useful to understand what was happening, and we agreed that it was good to speak the language of values, but people in the group wanted to avoid being manipulative. We were not engaged in marketing.

Sometimes members of the group had found it useful to appeal to the values of different parts of the map, for example, arguments around the economic and personal advantages of equality strategies had gained traction and led to policy change.

Using values could help people to engage in a conversation to bring about change. It was important to recognise that the polarisation of left and right did not necessarily reflect people’s values and that people had more values in common than we tend to think.

Neo-liberalism had been very successful in establishing a narrative based around values on the lower left-hand side of the map and a shift in that narrative also needed to be values based, starting from a different point.

A radical new narrative was needed focusing on universalism and benevolence and emphasising responsibility, enabling self-direction.

Our narrative needed to be a dialogue. One-to-one conversation between people can be the foundation to move into a new more relational narrative space.

It was important to tell authentic stories and to listen to the public and what matters to them. This tended to be things like home, family, place and where they work.

This dialogue is not the same as focus group politics. Radical listening skills are required, and discussions with a wide range of people, allowing their agendas to come to the surface, with sufficient trust to allow challenge and criticism to be expressed.

Note from Sharing Power Cell 2

Summary of key points

Lived experience is powerful in designing and delivering better policies and practices but needs to be used thoughtfully, through ‘reflective practice’ in ways that promote co-creation with professionals and ensure power is genuinely shared.

Organisations need to provide spaces in which genuine listening can take place in open-ended ways which avoid labelling, harming or exploiting people and which enable them to feedback on the process and find out how their input has been used, and from which everyone involved can learn.

Staff with lived experience are an important resource but need appropriate support to avoid trauma leaking out into work or being re-traumatised, or burn-out.

Funders can do more to involve people with lived experience, including making funding available for involvement in pre-project shaping activities, as well as post-project evaluation.

In more detail

Caroline Slocock, co-convenor of the Better Way, introduced the cell. She explained that the aim was to share insights with each other and inspire each other to do more, and that we would share learning from these discussions with the wider network and beyond (for example we had been feeding network insights into the Danny Kruger report for the Prime Minister about the role of civil society).

Our Better Way Call to Action pointed out that power is in too few hands, she said, and sharing power is one of the ways to redress that. At our first meeting Sue Tibballs reminded us that we have more power than we think. As a result of COVID-19 we might see more division and inequality in society, but there are also opportunities and we see some organisations changing their strategy.

The topic for this meeting was how we create inclusive conversations that drive change, and what is it about giving up power that makes us so uncomfortable?

Our guest speaker was Whitney Iles from Project 507. This organisation, set up by Whitney in 2011, works in prisons and community settings with young people who are leading lifestyles that are physically, psychologically or emotionally harmful to themselves and others. Project 507 employs people with lived experience and has taken that lived experience and turned it into trauma informed professional practice. It does not see itself as being there to help, more to create a space in which people learn and create together through co-production in a way that benefits everyone and with the aim of people becoming healthy, happy people.

Whitney said that Project 507 also help other organisations and policy makers to make use of lived experience but in doing so it’s important to think what we mean by this and who do we leave out. We will always miss some voices, some experiences.

She underlined the importance of lived experience for ‘filling in the gaps’ for policy makers and those developing practice, for example in the prison system. Lived experience can be invaluable, not least informing those around the policy table or who put policies into practice who would not otherwise know about the nuances of how things actually work in practice and whether they change lives, or not. Without this knowledge, the danger is that policies and practices either will not work or actually create harm.

And there is a big difference between tokenism (using people only for their lived experience, projecting labels on people eg ex-offender or ex-gang member, not ensuring people are emotionally safe and forcing people to disclose, ignoring the risk to the individual, failing to pay for the expertise) and empowerment (opportunities to learn and develop, with agreed labels, roles and job titles, creating reflective space for people to think about how they apply their experience, and providing clinical supervision and other support). Those who are ex-service users can often become overloaded with work and responsibility, and can suffer burn-out.

Reflection is vital to creating together and the best way to build in lived experience is through ‘reflective practice’ for participants to think about and process their experience, she explained, and this applies to practitioners too – thinking about why they bring young people to the table, what it means for us as ex-service users, including reflecting on the power dynamics in the group.

This should happen throughout and – critically - after the end of work, whether it is changing policy, an event, or practice, as this is an important piece of learning. Did those with lived experience feel heard, are there things that have been learned about working together? Sharing the learning is sharing the power and helps us to deal with nuances of why we don’t share power in the first place, she said. This learning should be set out in documents which should be shared and discussed with everyone involved.

Through reflective practice, she concluded, people from different backgrounds and experiences are able to come together and create something that is incredible.

Breakout sessions

Participants broke into smaller groups to discuss these topics further. Feedback from the breakout sessions, and the subsequent discussion facilitated by Steve Wyler, Better Way co-convenor, included the following points:

Creating the conditions for better participation

We need to create listening organisations in which people are heard as people and are truly valued. Framing the question can be problematic so have to start with an open book and provide space for people to speak, without stereotyping. Spaces where people can relate to each other as people, rather than according to their functional roles, can help to break down power imbalances.

It is important to see a person as separate from their circumstances. Avoid labels and definition by a particular lived experience. If you get to know a person it is possible to build the trust that is necessary for inclusive conversations. Attempts to share power become uncomfortable where there isn’t sufficient trust.

We need to remember that sharing power takes a long time.

Setting the agenda and an organisation’s strategy is best done with a mix of those who are service users, front line staff, managers and Board members, providing payments for people with lived experiences as well as opportunities to learn and develop.

Moving from listening to action – it is important to maintain the dialogue and feedback to build trust and help people understand they have made a contribution.

Involvement of others

It is important to listen with the right people in the room, but much can also be gained by people connecting to others not in the room, building linking social capital and so sharing power.

Often people want to talk about solutions and the systems – can we think about lived experience at a collective level not as heroic individuals?

We need to trust communities to know what they want and what they want to focus on, rather than impose a truth or theory of change on them, asking them to refine or test it.

In COVID-19 we need a blend of expert health professionals, as well as lived public health experience - things go wrong when one or the other is lacking.

If there is sufficient diversity people don’t have to feel grateful that they have been invited in.

In every meeting it is useful to have an empty chair, and ask the question, who isn’t here?

Managing the tensions within an organisation

Sharing power implies giving away control, and this comes with risks.

Within an organisation there is often a tension between the front line staff, who tend to have a depth of understanding and respect for the people they work with, and fundraising and communication teams who can treat lived experience as a commodity to be applied by the organisation for its own ends. This tension needs to be addressed at senior management or Board level, but rarely is.

As other Better Way discussions have explored, the dominant model of leadership is highly gendered, with centralising command-and control behaviours, and this needs to be challenged if we are to see more distributed forms of leadership, more conducive to sharing power.

Some pitfalls

Poverty-pimping is far too common. Staff members who are for example ex-gang members confer credibility and help attract funding for their organisation. As a result organisations often fail to encourage them to move on when they are ready for this.

Many organisations want their service users to tell their personal stories, but discourage their delivery staff from doing that. In fact, staff may have a great deal of lived experience they could share, and service users could play a much greater role in designing and shaping the delivery of services.

Organisations need to consider carefully what support is required. Without therapeutic training, trauma can ‘leak’ into work unproductively and this needs to be managed in a supportive and safe space.

There are concerns about how co-production is applied. When a professional has an agenda and gets people with lived experience into a room to design something according to that agendas this is not sharing power – those people might have wanted to design something different.

What does it mean to be an active ally? When professionals feel they don’t have legitimacy and pass the responsibility to those with lived experience that can do harm. It is tokenistic to think of lived experience as a trump card.

The term lived experience is not one some of those in the discussion liked because it is in danger of becoming just another label and we all have lived experience. It’s better to be more specific about what experience people have.

What funders can do to help

Lived experience is in vogue among some funders at the moment. But most still expect applications to come with fully worked out aims and interventions and outcomes, rather than investing in the process of working with a community to establish what these should be. This means that insight from lived experience becomes, in practice, an afterthought.

Funders could encourage organisations to include post-event reflection, as Whitney described, in their funding bids as a standard feature of the projects they fund.

Final reflections from Whitney

We need to understand better the intersectionality of gender and race, and avoid designating people in ways which places them in the impossible position of representing whole classes of people.

We have to be ready to do the difficult work, and be willing to give up control and power, however uncomfortable that makes us feel. In sharing power, and including people with lived experience and these whose voices haven’t been heard, there will be a spectrum of collusion, positive and negative, and many grey areas to navigate.

Next meeting

Wednesday 16 September, 2.00-3.30pm.

Topic: As organisational strategies change in the light of Covid-19, how can we use this shift to give more power to people in society?

Note from Changing the Narrative Cell 2

Note of the changing the narrative cell, 21 July 2020

Summary of key points

A drive for more funding can reinforce problematising narratives but it is possible to tell the story of change in ways that show where the need lies but does not disempower or problematise those who are supported.

Creating platforms for authentic voices who frame their own story can help disrupt existing narratives and shift power.

The media can problematise and ‘other’ people but can also be part of the solution – we can help them tell ‘human interest’ stories that show systemic issues and solutions as well as individual stories.

Individualism is part of the problem. We need to tell a different story of responsibility to each other, mutual obligation and caring for each other, as well as highlight the need for systemic change. This needs to appeal to people of different political persuasions if it is to take hold.

Funders can be part of the solution, for example, bringing in people with lived experience to help them make good choices.

Next time we will look in more detail into how to make change happen.

In more detail…

Steve Wyler started the meeting by summarising the key points from the last:

We want the national conversation to shift from 'them and us' to caring for each other, in which everyone contributes and also has responsibilities.

We need to create platforms for people to tell stories where they are the heroes, not our services.

We need to use new language, for example ‘valuable’ not ‘vulnerable’.

He said that at this meeting we were going to focus on the barriers to this kind of narrative and what we can do about them.

Neil Crowther reminded us of some the issues he’d raised previously, including the quote from a school nurse who had heard a boy during lockdown say that he was in school because he was ‘valuable’: that switch from seeing people as ‘vulnerable’ to focusing on their assets was a key shift in the narrative we are seeking. Other shifts were to hope, not fear, what we stand for, not what we are against, to solutions and opportunities, not threats, and support for everyday heroes. There is often a significant gap between the dominant narrative now, and the story we want to tell eg ‘social care as a vehicle for a good life’ rather than ‘social care as a destination or a place’.

Neil identified some of the barriers to and challenges for this kind of narrative:

For charities, fund-raising from the public was perceived to work best when describing problems and the agencies as the saviours.

Likewise, commissioners, procurers and charitable funders often wanted organisations to demonstrate the problem and show how their investment had solved it.

Influencing politicians to spend more on social issues often leads campaigners to play up the negatives and to portray services as solution, and in an age of austerity many services were under-funded.

Duncan Shrubsole then gave his perspective based not just on his current role at the Lloyds Bank Foundation but also as the Chair of Switchback and his 9 years at Crisis. He agreed that fund-raising was a challenge but added that the best charities do already major on turning lives around, but to get public buy-in they also have to tell the story of the journey individuals have gone through, including the negatives, and they have to show where they add value. That story had to be told in a humanising, empowering way. Likewise, when talking about issues with the government, who are trying to target tight resources, it is important that they understand and correctly identify needs. They have to understand the challenges people face.

There was sometimes a danger, Duncan said, that asset-based narratives reinforce a view that solutions were always in the hands of individuals. Promoting agency is important but this has to be balanced by also describing and addressing systemic issues that may hold people back. JRF described this a moving away from individual deficits to talking about what is holding people back. We do need people to be able to express injustice and harm, and for the narrative to identify what is getting in the way and what we can do about it.

Points coming out of the subsequent discussion included:

Creating platforms for authentic voices changes the narrative. It is important that the stories that are told stay true to people, and that people telling their stories are ‘talking in voice’, not mediated by others. Genuine voices disrupt the process. Sometimes charities frame stories in ways that justify what they do, when in fact they are not doing the right thing. The bigger picture is that people lack power, which is too concentrated in the state and vested interests, and giving people the opportunity to express an authentic voice can disrupt and shift this. Fixers helped people tell their own story in short films, with the framing done by themselves – see below. Sound Delivery is also providing platforms for lived experience– see below. Sometimes people don’t see value in themselves and lack aspirations or a feeling of agency. Grapevine Coventry and Warwickshire is training the people they work with to become the ‘leaders of the future’.

Targeting the media. We need to disrupt national narratives in the media and elsewhere which can be ‘othering’, disempowering and problematising. We should look not to news outlets but also daytime TV and popular magazines.

Telling the story of the system, not just the individual. Story-telling is important but it needs not to be just a human interest crisis story, it also needs to show what is wrong with the system in ways that point to solutions. Cathy Come Home is a famous example of how a story could lead to systemic change, in this case the Homeless Act. JRF is not trying to tell the story of poverty in a deeply human way, for example.

Reinventing society. The agenda of individualism underlies the current narrative and in the new framing we need to appeal to people to think beyond themselves and also not look to the state where family or grass roots support in communities might be a better solution.

A cross-party narrative of responsibility, caring for each other and mutual obligation. We need a narrative that crosses political divides if it is to take hold. Responsibility towards each other is part of the narrative of people caring for each other: you step forward to surface and resolve an issue because you want to prevent others from experiencing the same problem. Responsibility, linked to mutual obligation, is a concept that appeals to people of different political beliefs, whereas appeals for systemic change alone are often perceived as left wing. Taking responsibility is part of taking control and developing agency. The narrative needs to recognise that people do have choices, sometimes they make the wrong ones and have to take responsibility for that, but the system can also block opportunities or be unfair.

Supportive funders. Funders can be part of the problem, but sometimes they are blamed by charities when it’s not their fault. Some funders are trying to work in a different way, for example, democratising ways of distributing funds and bringing in people with lived experience to help them make choices.

It was agreed that the next meeting, which is at 3.00 -4.30 pm on 7 September, would focus on the practical dimension of how to change the narrative, and we might explore some specific examples.

Some relevant links

Fixers – see this blog by Margo Horsley.

Sound Delivery – links kindly provided by Jude Habib below:

An evaluation of our spokespersons network pilot – funded through crowdfunding and match funded via support from PHF and Lankelly Chase. We are now in conversations with funders to scale up from the pilot: https://beingthestory.org.uk/spokesperson-network

Two people from our network Brenda and Amanda featured on a Radio 4 Documentary – Unchained – about women and the criminal justice system https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000hghf

Being the Story Podcast – This podcast gives a platform to range of individuals with lived experience of a range of social issues – Think TedTalks for the Social Sector – available on all podcast platforms: https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/being-the-story/id1483449674 reflects the work to build confidence, find platforms and encourage visibility for those often not listened to.

Note from Changing Practices Cell 2

Note of a second Better Way cell on ‘Changing practices through relationship-centred practices and policies,’ held online on 16 July 2020

SUMMARY

We need to stop thinking of public and charity services as ‘fixing’ people and start connecting people up instead. This means we see people not as ‘consumers’ of services or ‘beneficiaries’ but as citizens and producers.

We shared examples where traditional service provision could be shifted towards models of community self-help, which would allow positive relationships to flourish, and which would respond to the needs and circumstances of the whole person.

There are good examples of this, not least the Self-Reliant Groups supported by WEvolution.

We need to ‘re-found’ the purpose of local government away from a gatekeeping to a more enabling role. We may also need enabling legislation, such a Community Power of Competence, to encourage a more widespread change in practice.

There is also a need for different job roles for those working on the public sector, and in the voluntary sector as well, to support this change.

In our next meeting we will explore in more depth what these job roles could look like, and also what might prevent the change we want to see.

1. AIMS OF THE CELL

Caroline Slocock, co-convenor of the Better Way, introduced the cell. Our Call to Action for a Better Way includes ideas around changing practices, putting humanity and kindness into services and building connection and community through relationships, not just passive services. This cell is a working group which will meet several times, to explore these questions in some depth, to help its members share their insights and experience, and develop new strategies which we can turn into a document to share across our network and beyond.

At the first meeting we’d noted that Covid-19 had strengthened some relationships, not least among those involved in local partnerships, and in some cases this has led to greater agency for more people, she said. Online relationships have worked well for some people, but not all. There is a short window in which to embed these changes as we come out of the pandemic, we thought. We also noted that building stronger relationships involves a different power relationship between the individual, civil society and the state.

Following on from this, the focus for this meeting was what the state and civil society can do to build stronger relationships.

2. OPENING PRESENTATIONS

We started the meeting with two presentations:

Becca Dove, Head of Family Support and Complex Families at Camden Council referred to an article by Jon Alexander from the New Citizenship Project

What we need to build is the Citizen story, where the role of government is neither all nor nothing, but in between: to equip and enable us, and to partner with us; to share as much information and power as possible, so that we can work together with government and with one another to create a new normal. … If you start from there, you don’t try to serve people-as-Consumers, you learn with people-as-Citizens.

So, asked Becca, if we were to see local authorities as public servants and public learners, what could that mean for the relationship with residents? What if, rather than just recruiting professionals, local authorities were to put as much effort into enabling families to support other families, where the professional’s job was to create the space and provide the support for families to help each other? In child protection, what if local authorities which currently commission advocacy for the families concerned were to direct their resources to supporting people with lived experience of child protection to advocate for one another? What if, rather than funding food banks, the role of the local authority was to support residents to create their own food co-ops and shops? And what if, rather than commissioning care packages, the role of adult social care was to find the strengths in residents and honour and strengthen relationships so that people could feel that their next door neighbour was as much there for them as their distant family many miles away?

When we think of residents as consumers, local authorities become, as Jon Alexander has described, branches of a retailer to central government’s head office, where the highest aspiration is to provide services efficiently and ‘cock-up less often’. But it need not be like that, and local authorities’ relationships with residents can be fundamentally different, Becca believes.

Noel Mathias from WEvolution identified prevailing areas of difficulty, including the following:

A negative mind-set: Our thinking is dominated by negative mental constructs (‘deprived community’ for example suggests dodgy places, unemployed people, single parents, crime, people on benefits). This need not be the case. In India for example the term ‘slum’ is associated with ingenious, enterprising and industrious places and people. But in the UK we tend to divide people into the weak and vulnerable on the one hand, and gatekeepers, regulators and messiahs on the other. This mind-set produces an imbalance in power and an imbalance in equality.

A culture of fixing: Our dominant culture is one of fixing, and this leads to dependency and entitlement. The benefits system for example is intended to help people, but ends up with people becoming dependent and feeling entitled, and less able to determine their futures themselves.

Deconstruction of the human person: If I have a mental health problem, says Noel, this is dealt with by a mental health charity. But if I am hungry I am passed on to a food bank, if I have a debt problem, I need to go to a debt agency. Each organisation will claim they are achieving their outcomes, but the person gets left behind.

WEvolution has developed a vehicle to bring about change: self-reliant groups. These are informal groups of people who come together to save small amounts of money, support each other, learn new skills, and become unexpected entrepreneurs. There are 135 such groups, in Scotland, England, Wales and Holland, and they provide spaces for people, mainly women, to meet, save and create. Some people end up becoming entrepreneurs. Self-reliant groups produce a series of shifts:

From simply being a consumer or beneficiary to becoming a producer and citizen;

From fixing to connecting;

From being treated in parts to the whole persons being empowered to act on their own.

The Self-Reliant Groups allow people to use the resources they have, rather than waiting for resources to be handed to them. They are not issue-based (e.g. focused on mental health problems or domestic abuse) but they can address specific issues, because they are used by people for whatever they think is best. SRGs across the country also share their experiences and learn from each other.

Learning from this experience, Noel recommends a focus on context, ceding power, and getting out of the way. We must recognise that people can often solve their own problems, without formal agencies doing it for them.

3. DISCUSSION

Participants broke into smaller groups to consider what the state and civil society can do to build stronger relationships. Feedback from the breakout sessions, and the subsequent discussion facilitated by Steve Wyler, Better Way co-convenor, included the following points:

3.1 WHAT MAKES FOR GOOD RELATIONSHIPS AND TRUST

Good relationships, it was suggested, emerge from:

Parity of relationship, with an equal footing between the state and community - traditional ways of working imply control by the state.

Permission, to challenge, to do things differently, with authority and accountability.

Partnership, based on equal trusting relationships.

Good relationships are more likely to be produced when people come to the table willing to listen to others rather than determining beforehand what they want. And also when there is respect for those working on the ground.

Strong relationships are those which emerge from tension, not those which avoid tension. Keeping conflict buried is foolish and never works.

3.2 Learning from existing examples

Experience from India and elsewhere suggest that the model of self–reliance can become widespread and highly influential on public services, and financial institutions, for example. For this to happen in the UK we will need to keep things simple, easy to establish, informal, and civil society organisations will need to co-ordinate their efforts better, rather than fight for themselves.

Organisations like Groundswell are demonstrating that it is possible to create the conditions for people in difficult circumstances (in this case long term experience of homelessness) to become effective in supporting other people with similar difficulties in their lives.

In Leeds there are 37 bottom-up neighbourhood networks, often led by older people. There is a lot to be learned from models such as these, about fostering connections and improving lives.

3.3 What makes things difficult

The centre needs to get out of the way so that those on the ground can get on with things and even break the rules. This requires a leap of faith and is not an easy step to take. For those in the statutory sector formality of structures can make this difficult, and for those in the voluntary sector, the funding regimes can be a problem.

Getting out of the way does not mean being absent. There will often be a need for professionals in some shape or form to support peers to work well with each other, and to help manage stress associated with the work, and even to provide oversight and supervision.

State-based community development tends to be short term and often fails to leave a legacy, especially where things are done to a community, not with them, or where professionals do not recognise the ability of people who are not professionals.

3.4 Re-thinking the role of local government and civil society

We need to lift our sights high, and consider how to ‘refound‘ local government, moving away from a ‘gatekeeping’ to an ‘enabling’, not ‘extracting’ role – and identify the principles at its heart that we want to revive and sustain.

It was felt that in re-imagining local authorities we need to reduce the distinction and distance between those working in local government and those in community roles. Local government could be redefined as part of a common local effort, working with and alongside other local agencies. Perhaps there ought to be ‘A Chief Relationships Officer’ to help facilitate this. There needed to be a permission to challenge.

Indeed, the problems of centralising command and control practices, and delivery of atomised services, are not confined to the public sector. They are also to be found in the charity sector. Those who want to shift towards more distributed models of self-reliant social support and community building, working with the whole person, will do well to make common cause, whatever sector they are from.

What if the community had a Power of Competence? The onus would be on the local authority to provide that a self-reliant group could not make use of a community centre, not on the group to prove that it could.

What if there was a statutory requirement for local authorities to create an Easement function? In other words, if a community group could explain that a rule really doesn’t work for them, and the local authority would be required to consider easing the rule.

There is often a deeply engrained but narrow sense of what the job is. We need to identify new and better public sector and civil society job roles, specifying the types of proactive enabling functions which can help to foster and support community self-help.

4. TOPICS FOR FURTHER MEETINGS OF THE GROUP

The following topics were suggested:

What are the proactive enabling roles which we would like to see public sector and voluntary sector agencies adopt, which can enhance the ‘What If’ types of relationship building and community self-help we have described above?

And what are the Why Nots? – in other words what are the obstacles which will get in the way?

We agreed that in the meantime blogs and video interviews would be helpful for the work of the group, and to help share our thinking more widely. All members of the group are encouraged to contribute in this way. NB See this subsequent blog by Caroline Barnard.

5. NEXT MEETING

Thursday 17th September, 3.00pm-4.30pm.

Note from Collaborative Leadership in Place Cell 2

Summary of Key Points

Leadership is important but great leadership is about enabling others.

When individuals change, collaboration is likely to continue where a clear, shared purpose has been created across organisations and has become part of the culture and where good relationships at all levels have already been forged. Language should be simple and shared, so that everyone understands the vision.

Relationship-building and the connector role need to be recognised and funded.

People must stop seeing themselves as organisational representatives and instead act as ‘systems leaders’ and ‘systems stewards’. Lasting change only happens through distributive leadership.

The focus must be on ensuring the system matches the needs of communities and individuals served, not organisations, and they need to be engaged and their voices heard.

Governance can very important where formal partnerships are established, and succession planning is too often neglected.

Next time, we’ll be looking at what good collaboration, systems and distributive leadership looks like in practice.

In more detail

Steve Wyler introduced the meeting by summarising some of the key messages from the previous discussion:

Relationship building is critical to good collaboration

This relies on openness, trust and honesty

Collaboration had been speeded up under Covid-19 and one of the reasons is that there is a clear common cause

One question was how to build on this as circumstances changed

Steve explained that the focus of today’s discussion was what happens when key individuals move on? He said that the thought leader for this cell, Cate Newnes-Smith, the CEO of Surrey Youth Focus, was now experiencing this challenge in the most tragic of circumstances. The Director of Children’s Services in Surrey, with whom she and others had been working across sectors to transform opportunities and services for children and young people (known as Time for Kids), had suddenly died. He invited her to speak about Dave Hill, the lessons she had learnt from him and about the future. A blog she has written in tribute to Dave Hill and his work can be read here.

Cate said that great leaders are about enabling others: Dave had created space in the system for others to do things. He had also brought in a really good team of people and had established a network of relationships between people in Surrey which meant that hopefully the reforms he had initiated would continue after his death. Since Dave’s death, for example, she had recently presented about Time for Kids to the SEND partnership board and pledges had since flooded in to take it forward.

Nonetheless his successor would be important, and Cate is hopeful that a successor to Dave will be chosen who wants to carry on taking the work in the same direction. Another plus factor is that as the political control of the council in Surrey tends to remain stable, the councillors and other senior leaders are unlikely to change in the next few years.

In conclusion, Dave had been a driving force, but she also thought that Dave had created such impressive momentum in the system and had put the right people in place to make it happen without him.

Points made in the subsequent discussion included:

Relationship-building is essential and takes a long time and we need to find ways of getting this funded as part of the business model. Individuals at all levels in the collaborating organisations need to see relationship-building as part of their job. Voluntary organisations were sometimes performing what a Better Way is now calling the ‘connector role’ but this is often not recognised or rewarded. Indeed, contracts or grants tend to be awarded for specific purposes which do not include relationship-building. Surrey Youth Focus was fortunate in that it was now being funded to do that connecting role by the council; and the Community Foundation for Surrey was increasingly seeing part of its role as convening. A national example of government funding organisations to work together was DCMS’ place-based giving initiative which had given core funding to finance posts to facilitate collaboration for local-funding-raising.

The role of systems leadership must also be promoted but funding mechanisms can get in the way, encouraging competitive behaviours. Surrey Youth Focus see ‘systems stewardship’ as part of their role, and what that meant for them was to ensure that ‘voice of the child is in the room when they are there’. This needs to be built into commissioning and procurement, as was being done in Surrey in a co-operative bid for CAMS work. With systems leadership also comes distributive leadership at all levels, which also helps to embed change and ensure it does not rely on any one individual.

A shared purpose inside and across organisations which helps people to focus beyond their organisational agendas is crucial to good collaboration and it also helps to sustain collaboration when individuals move on. Changeover of staff in local authorities could be a serious problem. One person had worked with a council where three different CEOs were put in place over 5 years, with restructurings as well. A lesson based on experience from the Wigan Deal is that two things are crucial a) a culture linked to a clear bigger purpose and b) ownership of the agenda outside of the council of that purpose, as well as within. If a bigger purpose is ingrained in the culture of the organisation, it naturally encourages people to work in a different way, including new people coming into the organisation. A clear culture based on purpose ensures recruitment of new staff will result in a continuity of vision. Different parts of the local authority also work more seamlessly together where this is the case because staff share that bigger picture. Language matters and needs to be clear, simple and shared across organisations.

This purpose must be based on the needs of those served and it is important that their voices are built in through participative processes and through organisations who see it as part of their purpose to facilitate and represent those voices.

Succession planning could also help ensure continuity but was neglected, and it was important to get governance and systems right, for example through co-chairing where there were formal partnerships, for example, where funds were jointly managed. That said, some collaboration could be driven by less formal mechanisms. Time for Kids had no structure or governance and would only be effective if it influenced the agenda of existing bodies and partnerships such as Health and Well-Being Boards. In that case, clear principles and vision were important.

The group finished by identifying this issue for discussion at its next meeting on 9th September at 3.00-4.30pm:

What does collaboration look like? How does it differ from other similar practices such as partnership or consultation?

What does systems leadership look like? How do we know it when we see it, how do we know when we don’t?

What does distributive leadership look like? What does it require in the way of leadership and followership?

Note from an online roundtable: Coronavirus - building community and connection 4

4th Meeting to inform Danny Kruger’s proposals for the Prime Minister

Held on Thursday 9th July 3.00-4.30pm.

Founding Better Way member Danny Kruger MP was invited by the Prime Minister to ‘develop proposals to maximise the role of volunteers, community groups, faith groups, charities and social enterprises, and contribute actively to the government’s levelling up agenda.’

Building on recent network discussions we produced a draft paper which we shared with Danny as work in progress. This meeting, attended by 74 Better Way members, was an opportunity to further inform Danny’s proposals, and also to help the Better Way feed in thinking to other politicians in this space.

As a result of the meeting, which Danny joined at the end, we produced this 2-page paper which is a summary of our thinking on what government can do to support connection and community.

Note from Changing Organisations Cell 1

First meeting of the Better Way ‘Changing Organisations’ cell, 8 July 2020

1. SUMMARY OF KEY POINTS

Some organisations are practicing ‘radical listening’ – creating informal spaces for the people they work with to talk about their own experiences and ideas, and be heard, and develop an agenda for action accordingly.

This can result in better services, capable of responding to people on their own terms, building their agency, and bringing humanity to the organisation’s work.

This is very different from the widespread practice where organisations have their own agenda and seek to engage service users in it, effectively treating them as ‘other’.

In order to practice radical listening well, organisations need to break down the boundaries between themselves and their ‘service users’. This includes employing more people from the communities they serve.

Radical listening can happen on-line, as recent experience has proved.

Some funders are enabling organisations they fund to work in this way. Statutory agencies can too, although they often find it hard to do so.

2. IN MORE DETAIL

Caroline Slocock, co-convenor of a Better Way, explained that the group had been set up to explore further the Better Way Call to Action theme of ‘changing organisations to focus on communities and solutions’, and in particular looking outwards, putting those we serve first, listening to and reflecting them in everything we do.

COVID-19 has been an opportunity to do more of this, and to think how organisations can operate differently beyond the crisis. We hope this cell will not only enable participants to share insights with each other but will also provide material that we can share with the wider network.

Caroline introduced Karin Woodley from Cambridge House, who has agreed to act as a ‘thought leader’ for the group. Her presentation included these points:

In recent years organisations have had to navigate hostile economic, regulatory and policy environments and many have responded by implementing strategies driven by a financial bottom line. They have become distanced from service users, and handed over the definition of impact and values to funders and commissioners.

COVID-19 has the potential to make this situation even worse, with organisations protecting themselves rather than service users. But, said Karin, this could also be a moment to work with communities to shape a new era.

Karin explained that radical listening is a process to put those we serve first and to create connections, disrupting stereotypes, and empowering and transferring agency to those most affected by social injustice and poverty.

It is an opportunity to challenge paternalistic cultures, gain control of our destinies, working hand in hand with service users, rather than delivering a plan to a passive group of the under-privileged.

Our hearing has been contaminated, said Karin, and we have failed to listen to the lives and experiences of our service users. We have said too much ourselves, and not listened properly. Instead we have filtered what we hear with our preconceived notions.

We need to become the vehicles through which the communities in which we are based speak, and not act as their translators and gatekeepers.

But who is doing the listening? Often our staffing structures are White, middle class, well-meaning and liberal. This too needs to change.

Radical listening means you don’t reflect back, you don’t summarise, you don’t reshape sentences. Instead it means allowing people to get to the end of their sentences, to talk about their whole life experiences, to tell their whole stories.

Karin shared two examples where radical listening has led to change:

Cambridge House provides a statutory mental health advocacy service under a government contract. Karin baked a cake and held a discussion with a group of older Black women, to create a space for them to talk to each other and reflect on their experiences at the Maudsley Hospital. As a result it became clear that the advocacy service needed to change to address matters such as food and diet, which had previously been neglected.

The law centre at Cambridge House was providing generalist advice on housing employment and benefits. But after holding a discussion with service users it turned out that generalist advice was not what people really wanted. They wanted court action. So Cambridge House has moved away from generalist advice and became a specialist in taking legal action, eventually winning a landmark case against the local authority in the Supreme Court, changing the definition of statutory housing rights for those who are homeless, disabled or with a mental health condition.

During COVID-19 the initial response from staff at Cambridge House was that services could not be delivered without face-to-face contact. But virtually all service users had phones, even those who are poor, or in care homes, or homeless, and so the organisation moved to digital services. There was urgent need – in some care homes people were dying, criminal landlords were increasing their activities, families were losing tenancy rights as a result of a COIVID death, and there was a rise in COVID-related suicides. There was high demand for support from Cambridge House. Because staff didn’t have the expertise, service users played a big role in designing on-line services, establishing multiple ways of communicating with Cambridge House. There is now more service user engagement and feedback, not less.

Looking forward, Cambridge House is considering how it can ensure that service users will be able to speak to the organisation on their own terms, using their preferred methods of communication, combining wider on-line reach with building-based delivery, and at the same time refocusing services to protect human rights, and provide more opportunities for people to speak out themselves and take action to bring about change.

In the following discussion participants made the following points:

ORGANISATIONS CAN BECOME MORE WELCOMING AND MORE RESPONSIVE

Some organisations claim to put people at the heart of everything they do, and wish to give the appearance of this, but don’t actually practise the type of radical listening that Karin has described, and carry on doing what they want to do, according to their own agenda. Many organisations operate from buildings and pride themselves on offering welcoming spaces, but actually they are only really welcoming for those who come to do the things which the charity has arranged at particular times. But in the recent crisis many organisations have discovered that they can be adaptive and flexible and have been learning to listen better, and when they do so, they become more welcoming and add more value for their community.

ORGANISATIONS FACE CHOICES IN HOW THEY TRANSLATE RADICAL LISTENING INTO ACTION

It is not enough to be listened to – the ability to make things happen and bring about change is what matters most. In recent Better Way discussions we have talked about solidarity. Many charities operate vertically, people in positions of privilege doing things for the poor. The alternative, it has been suggested, is solidarity, people combining with others to do things for themselves. This is essentially a community development approach. But some felt that this, by itself, is not sufficient. When, for example, someone comes home to find their landlord has put all their belongings out on the street, they just want someone to provide a roof over their head. And where there is a pattern of injustice, organisations can work with service users to take targeted action to bring about a wider change.

EMPOWERING FRONT-LINE STAFF IS PART OF RADICAL LISTENING

It is easier for organisations to listen if their front-line is empowered and are therefore more able to develop relationships and to respond flexibly. Equally it can be a big challenge for larger organisations to listen – and learn – from their front-line staff. You have to invert the normal order.

ORGANISATIONS CAN REDUCE ‘US AND THEM’ BARRIERS

Organisations can do more to break down the perception that their staff and their services users are different in kind. We need organisations that are open and inclusive, capable of behaving as if staff and service users are all part on one family. Lived experience inside organisations is important.

We will need to appreciate that experiences of lockdown have been very different. For some it is been a relatively pleasant few months, for others a troubling and confusing time, and for some the worst experience of their lives. We will need to find ways to allow people to listen to and appreciate these different experiences.

FUNDERS CAN CREATE FAVOURABLE CONDITIONS FOR RADICAL LISTENING

In the COVID crisis some independent funders have been changing the nature of the conversation with those they fund, listening to charities more, allowing them to work responsively, and not holding them to plans set three years ag

STATUTORY ORGANISATIONS CAN ADOPT RADICAL LISTENING, BUT FACE PARTICULAR CHALLENGES

One of our participants shared an example from South Korea, a country which has had an authoritarian history, and where citizens have not been used to public participation. Nine years ago Seoul City declared itself to be a ‘listening city’. A symbolic ‘Big Ear’ was placed outside the city hall, where citizens could make complaints or share ideas. The Mayor of Seoul set up a mobile office, meeting local residents in different neighbourhoods, and even spent some weeks living in poor housing in deprived neighbourhoods. But after four years, it became clear there were limitations to this listening exercise. It was also necessary to shift the internal system of how City government works, for example establishing participatory budgeting, and building relationships between City officials and citizens and local community groups. This remains work in progress.

In this country statutory organisations find radical listening very difficult, in part because they have formally prescribed agendas. They can sometimes provide licence to others to operate without formal plans, and to act in response to what they hear from the people they work with. But such experiments are nearly always of short duration, and rarely translate into mainstream practice.

It was suggested that radical listening can flourish best in the spaces between formal institutions.

ORGANISATIONS ADAPTED DURING COVID-19, ALTHOUGH THERE WERE DIFFERENT DRIVERS FOR THIS

During the COVID-19 there has been a notable difference between organisations which have adapted by listening to and learning from their ‘front lines’, and those that haven’t. The government response to the spread of the epidemic in care homes was a tragic example of the latter, when they failed to listen to front line voices, until people were dying in large numbers. If ever there was a time when ‘the last should be first and the first should be last’ this was it, it was argued.

At the same time, COVID-19 has also shown that financial drivers can produce positive change. Some parts of the private sector, for example supermarkets and private schools, have been able to re-engineer their business models with great success, at scale and at speed, listening to and responding to customer demand in ways that arguably would not have happened in the public and voluntary sectors. However, it was also pointed out that people working in many charities have also shown themselves to be nimble in COVID-19, willing to be pushed and be challenged.

ORGANISATIONS MUST NOT REVERT TO THE PRE-COVID MODELS

Over many years we underachieved in terms of social equity. If we had been more successful we wouldn’t have seen the obscene level of inequity we have seen in COVID-19. Organisations, it was felt, must ‘steal the moment’ to do better, not revert to how things were done before.

Suggestions for topics for further meetings:

Can we distil the essence of radical listening, learning from different examples?

What is needed to change the composition and roles of staff and boards in organisations to support radical listening?

How can statutory sector organisations create more space for radical listening.

We will invite others from our network to join the group.

NEXT MEETINGS

The next meeting will be on 8th September at 3.00-4.30pm.

We also agreed to arrange a third meeting in November (date to be set).

FURTHER READING

Note from Changing the Narrative Cell 1

First meeting of the Better Way ‘Changing the Narrative’ cell, 25 June 2020

Summary of key points

We want the national conversation to shift from 'them and us' to caring for each other, in which everyone contributes and also has responsibilities.

We need to create platforms for people to tell stories where they are the heroes, not our services.

We need to use new language, for example ‘valuable’ not ‘vulnerable’.

At future meetings we are going to focus on the barriers to this kind of narrative and what we can do about them.

2. In more detail

Steve Wyler, co-convenor of a Better Way, explained that we hope the new cell will not only enable participants to share insights with each other but will also provide material that we can share with the wider network. The group had been set up to explore further the Better Way Call to Action bullet point - ‘to see the potential in everyone and stop services becoming a ‘problem industry’ – also reflected in the Better Way principle ‘building on strengths is better than focusing on weaknesses’.

There were three levels to the change a Better Way would like to see, he explained:

Individual practitioners to change their relationship with those they serve;

Providers of services in the voluntary and public sector to stop using narratives which present people as problems or ‘vulnerable’;

Government and opinion formers to stop using a national narrative which too often portrays recipients of welfare and people experiencing poverty or issues in their lives negatively.

The group would be focusing primarily on the last two – how to change the overall narrative.

He introduced Neil Crowther from Social Care Future, who had agreed to act as what we are calling a ‘thought leader’ for the group. His presentation included these points:

The language we use, the ‘framing’ is incredibly influential, reinforcing familiar stories and emotions which influence how we see things e.g. talking of crime as a ‘virus’ points to social solutions, as opposed to presenting it as a ‘beast’, which points to police intervention.

Hopeful narratives are empowering, and ways to foster hope include focusing on solutions, opportunities and what we stand for as well as emphasising the role of everyday heroes.

Social Care Future is seeking to shift the narrative which currently presents social care as being in crisis, broken and about to collapse and which puts the sector centre stage, not the people served, presenting it as a Cinderella service. We talk of caring for the ‘vulnerable’, which creates a them and us.

Talk of the ‘vulnerable’ has peaked in the Covid-19 crisis but another story has also emerged, of mutual aid and caring about each other, not just caring for.

The latter provides a different basis for how we think about people in the adult social care system, and indeed elsewhere – as caring for each other, reciprocity, ‘valuable rather than vulnerable’. Reciprocity is key, where instead of offering someone help, you ask them for a favour.

We need to look at who are the heroes of our stories, and who is telling it? Is it the professional, or the agency, or the people whom they serve? It should be the latter.

Looking at the wider national conversation, and the stories service providers tell about those they work with, he hoped we could move to a hopeful narrative of solidarity, in which we care for each other, and in which we foster a sense of agency, rather than painting people as problems.

As an example, he showed an advert made by NSPCC which portrayed a boy supported by the charity as achieving his dream of becoming an astronaut.

We then broke into three breakout groups to consider ‘What is the story we want to tell?’ These were some of the points made in the following discussion, facilitated by Caroline Slocock, Better Way co-convenor:

There was broad agreement about the need for a new narrative around mutual support, breaking down the ‘them and us’ and telling a story of ‘all of us’ which can help to build agency.

We have seen how digital tools can democratise storytelling, especially among young people.

We should avoid presenting people as ‘case studies’ and stereotyping them. It is important to give power to people to tell their own stories in their own language, whilst also managing risks and practising safeguarding.

That often involves giving up power and instead creating platforms for others. Too often, organisations working with people feel that ‘they know best’ and this is a holding on to power. They are attracted to ‘rescuer narratives’ which cast the organisation as the hero in the story. They encourage people they work with to tell a negative story about themselves, e.g. the homeless young person retelling their sad story, and this reinforces rather than helps to overcome problems.

Changing the narrative also requires a culture and systems change and this cannot be done by one organisation in isolation. We need to work together on this.

The people who have experienced difficulties in their lives are often incredibly resilient and strong, but we insist on presenting them as vulnerable.

Stories have heroes as well as villains. The system should be the villain, not the individual, but too often we blame them.

Language was important and often got in the way. It is hard to change our own internal narratives.

We should look at the bigger picture of a culture of individualism over the last 40 years which is all pervasive and which underplays the importance of relationships and how people find fulfilment through them. We need to emphasise the responsibility we have toward each other and also help people find their sense of purpose.

Next time the group wanted to look at the barriers to the hopeful narrative of mutual help – what stands in the way of making it happen, and what can we do about it.

3. Dates of next meetings:

Tuesday 21 July, 3.00-4.30pm

Monday 7 September, 3.00-4.30pm

4. Further reading/viewing

Neil Crowther shared some links after the meeting:

The Vulnerables – an article by disability rights campaigner Baroness Jane Campbell.

A selection of various podcasts and blogposts at #socialcarefuture

An example of someone who uses services being heard: Anna Severwight reframing the discussion on funding at the Commons Health and Social Care Committee

Margo Horsley shared some links which describe the work of Fixers, an initiative (no longer running) which enabled young people to tell their stories, and to be heard, understood and respected by others.

What is Fixers: https://youtu.be/39sYPhAg-Sw.

Some fixers reflecting: http://www.fixers.org.uk/index.php?page_id=3244.

National platforms: http://www.fixers.org.uk/feel-happy-fix/fixing-child-sexual-exploitation/home.php .

A campaign on sex education in schools (the Government Minister at the time, Maria Miller, believed that it was individual voices that had made change happen despite all the work put in by other institutions over the years): http://www.fixers.org.uk/index.php?module_instance_id=11208&core_alternate_io_handler=view_news&data_ref_id=16291

Note from an online roundtable: Coronavirus - building community and connection 3

Note of a third online roundtable on the coronavirus crisis and the power of connection and community, 18 June 2020

Summary

We started with speakers who set the scene, then went into four breakout groups, and came back into a plenary discussion in which the groups reported back. The key messages were:

A common purpose in the Covid-19 crisis is driving collaboration. Can we create a future common purpose as we emerge from the crisis?

The surge in mutual aid, and the Black Lives Matter protests, have raised fundamental questions about the role of many institutions. A shift in power, and a letting go, is clearkly required. But there will be resistance.

The state and charities have a tendency to ‘colonise’ human connections to validate their own work. But we know from excellent examples it need not be like this.

The recent procurement guidelines have encouraged collaboration rather than competition, and these need to be maintained.

The role of local community anchors as ‘cogs of connection’ has been undervalued. And we need to better appreciate the different roles that individuals, community groups, established voluntary agencies, businesses, as well as local and national government can best play.

2. In more detail

Caroline Slocock, co-convenor of the Better Way, introduced the discussion. She explained that this was a third meeting on Covid19 and the power of connection and community. Our Call to Action for a Better Way called for a radical shift to liberate the power of connection and community and in recent weeks across the country we have seen inspiring examples of this, despite physical distancing.

The discussions have highlighted both opportunity and danger. Many of the things we have set out in our Call to Action (collaborative leadership, sharing power, changing organisations and shifting practices in favour of human relationships) are happening, sometimes faster and better than we could have imagined. There has been more solidarity and sense of purpose, flexibility, creativity, a speed of response, new connections and collaborations, as well as more humanity and kindness. But the future is more likely to be a negative one, with more inequality, more command and control, and more suffering. So what can we do collectively and individually to turn this into a moment where things go better in the future, not worse? And in particular this meeting will consider how we can we build on the collaborative leadership that is already happening, to change for good.

Nick Plumb, Locality

Nick highlighted findings from the new Locality report ‘We were built for this’. Local collaborative relationships are being built in many places, driven in part by shared purpose across sectors and across public agencies. Collaboration has especially flourished where there were pre-existing relationships with community organisations. Community organisations were often able to take the lead and move quickly, not waiting to ask permission. National procurement guidance issued at beginning of the crisis allowed greater flexibility and this also helped to create favourable conditions for partnership.

The report contains recommendations on community powered economic recovery, on ways of turning community spirit into community power, and on collaborative public services. These include a shift from the competitive mind-set which has underpinned public services for many years to a new collaborative mind-set. In the wake of a decade of cuts in public spending the report calls for a review of local government finance including new fiscal powers to reverse cuts to preventative services, and tackle inequality. The recent very welcome cabinet office guidance on procurement should be further embedded, rather than a return to normal. Government should also promote models of service transformation partnerships between councils, community organisations, and health agencies and peer learning programmes such as the Locality-hosted The Keep it Local Network should be expanded. There are several opportunities to influence government investment and policy to support a shift in favour of local collaboration, including the long-promised UK Shared Prosperity Fund, the forthcoming Community Ownership fund, and the forthcoming Devolution White Paper.

The report also explains that community-led anchor organisations can play a critical role in establishing ‘cogs of connection’ in a locality, but as Nick pointed out this not always recognised and rarely funded through public sector contracts, and that needs to change

Becca Dove, Camden Council

Becca is head of family support and complex families. She described a recent Zoom call led by the manager of Kentish Town Community Centre, with local residents, a council colleague who runs food hubs, a local GP delivering social prescribing by bringing people together in a garden, and partners from University College London. In the meeting there was no distinction between the council staff, residents, community workers, and academics. ‘Lanyards were left on the floor’, said Becca, and people made on the spot offers to help each other: ‘I can do that for you.’ There was a strong sense of the commons, of everyone seeing themselves as stewards, wanting to leave Kentish Town in a better place, and seeing connection and relationships as the way to do that. Becca wrote an article in April, recognising that the state doesn’t always have the answer, and that during the emergency the community have given the solutions to a problem in countless ways. The job of the council is to lend hand and hearts to the constant collective effort, making a contribution, respecting what residents need and want, and recognising the widespread goodness in the community. New public management forced everyone down the wrong road, but there are a lot of public servants who think and feel as Becca does, she feels.

3. Achieving more collaborative leadership

Participants broke into smaller groups to discuss the question, ‘What can be done nationally and locally to achieve more collaborative leadership in the coming months?’ Feedback from the breakout sessions, and the subsequent discussion, included the following points:

Common purpose

There is an underlying power imbalance, and while people have generally put aside competitive behaviours and organisational roles in the crisis, we can’t assume that will continue in future.

A sense of shared endeavour in the face of a common enemy has been critical to encourage collaboration. We will need to establish a new common cause in the months ahead, one capable of determining how we behave towards each other and which will maintain the shift from ‘I AM’ to ‘WE ARE’.

We will need to describe and name the future we want to see as clearly as possible.

Letting go

In times of crisis institutions have discovered they do not have the flexibility to respond to community action, and when they do respond, they often do so in ways which seek to validate themselves. They need to learn to let go and trust. Where that has happened it leaves a positive legacy and the foundations for a different kind of relationship.

The conventional charity model may not be the way forward. It has been challenged by the wave of mutual aid, and by the recent Black Lives Matter protests. Some organisations are thinking deeply out their purpose and role and how they work. But there are many in institutions of all sectors who are not ready or willing to let go, and will want to hold on to their power.

Understanding different roles

There are different and distinctive roles that can be played by community self-help, established community organisations, and the public authorities.

There is an unresolved debate about role of the state. Is the role for local government, for example, to protect citizens, by taking action directly, or should it adopt a more hands-off role which allow people to take action on their own terms?

It was suggested that charities achieve most when they see their role as meeting the purpose of individuals.

Businesses have been compelled to rethink their purpose, and a new alignment between communities and businesses might be possible.

Commissioning and procurement

The prevailing commissioning system is hard-wired to drive competition between groups, and that produces weak and transactional relationships. But good commissioning can encourage collaboration. Human Learning Systems, developed by Better Way member Toby Lowe, with Collaborate, presents an alternative to new public management methods, and sets out a better path for commissioning and procurement.

The Moral Economy

It’s not always about money, but it is always about connection, it was felt. The term ‘moral economy’ describes economic activity that can take place without money changing hands. This can happen on a very big scale (for example in the Arba’een pilgrimage in Iraq which can include 20 million people and where people are fed without money for days on end).

Civic immune systems – the precious nature of relationships between human peoples, can be infected and damaged by funding, interventions of voluntary agencies, or the state. Individualism on the political left and right has led to outsourcing many things that we used to do as families and communities. We should not seek to go backwards, but human life is enriched when we do things together. The distinctions between labour, work, and action made by Hannah Arendt may be helpful in our thinking on this.

Creating conditions for collaboration to flourish

Community spaces and other forms of local infrastructure can encourage connectivity and help to build a more equal and mutually supportive society, as Eric Klinenberg’s book Palaces for the People explains (and see an interview with him here).

We need to understand what it takes for people to relate to each other well. The language we use can help, or can get in the way. Many terms in widespread use (like complex families, vulnerable people) reinforce them-and-us divisions, and we need to frame our story in different ways.

A strong signal from central government in favour of collaborative practice, in service of local communities, and to create the conditions for people to do things on their own terms, would be helpful, and would confer permission for those in the public sector and beyond to do things differently. But it is best not to depend on that, it is always better to seek forgiveness than to ask permission.

Some things, mutual aid groups for example. are best left alone, and certainly not regulated.

4. Next meeting

We agreed we should organise a further meeting, in a few weeks’ time. Suggested topics for discussion:

The unifying shared purpose beyond the COVID-19 crisis.

The changing and distinctive roles of individuals, community organisations, charities, and the state, and the contribution each can make to the social architecture we want to see in the future.

Better Way members are invited to contribute blogs and video clips on these or related topics.

Note from Changing Practices Cell 1

Note of a first Better Way cell on ‘Changing practices through relationship-centred practices and policies,’ held online on 10th June 2020

SUMMARY

Covid-19 has strengthened relationships, including local partnerships, given more agency to employees and led to professionals working in new ways that are giving the people they work with more agency. Online relationships have worked well for some people but not all, and we’ll need blended services in future. There is a short window in which to embed these changes as we come out of the pandemic and, amongst other things, we need to tell the story so that we inspire others to do more. Building stronger relationships involves a different power relationship between the individual, civil society and the state which is one of the issues we will be exploring next time.

1. AIMS OF THE CELL

Caroline Slocock, co-convenor of the Better Way, introduced the cell. We hope to build on an earlier Better Way roundtable about relationship-centred public policy in the coronavirus emergency and beyond. Before Covid-19 Caroline wrote a report on deep value relationships bringing together the insights from many sources, including David Robinson’s Relationships Project, and one of the conclusions was that we have a moment where potentially we could redesign existing services around relationships, and that we can build on existing practice, but need to do more together to build the case to make this widespread. Our Call to Action for a Better Way includes ideas around changing practices, putting humanity and kindness into services and building connection and community through relationships, not just passive services.

This cell is a working group which will meet several times, to explore these questions in some depth, to help its members share their insights and experience, and develop new strategies which we can turn into a document to share across our network and beyond.

2. OPENING PRESENTATIONS

We started the meeting with two presentations:

DAVID ROBINSON